brochure "Partizanski spomenik u Mostaru" (1980)

book “Spomenica Mostara 1941-1945.”

another document or proof of the memorial stone (e.g., a photograph).

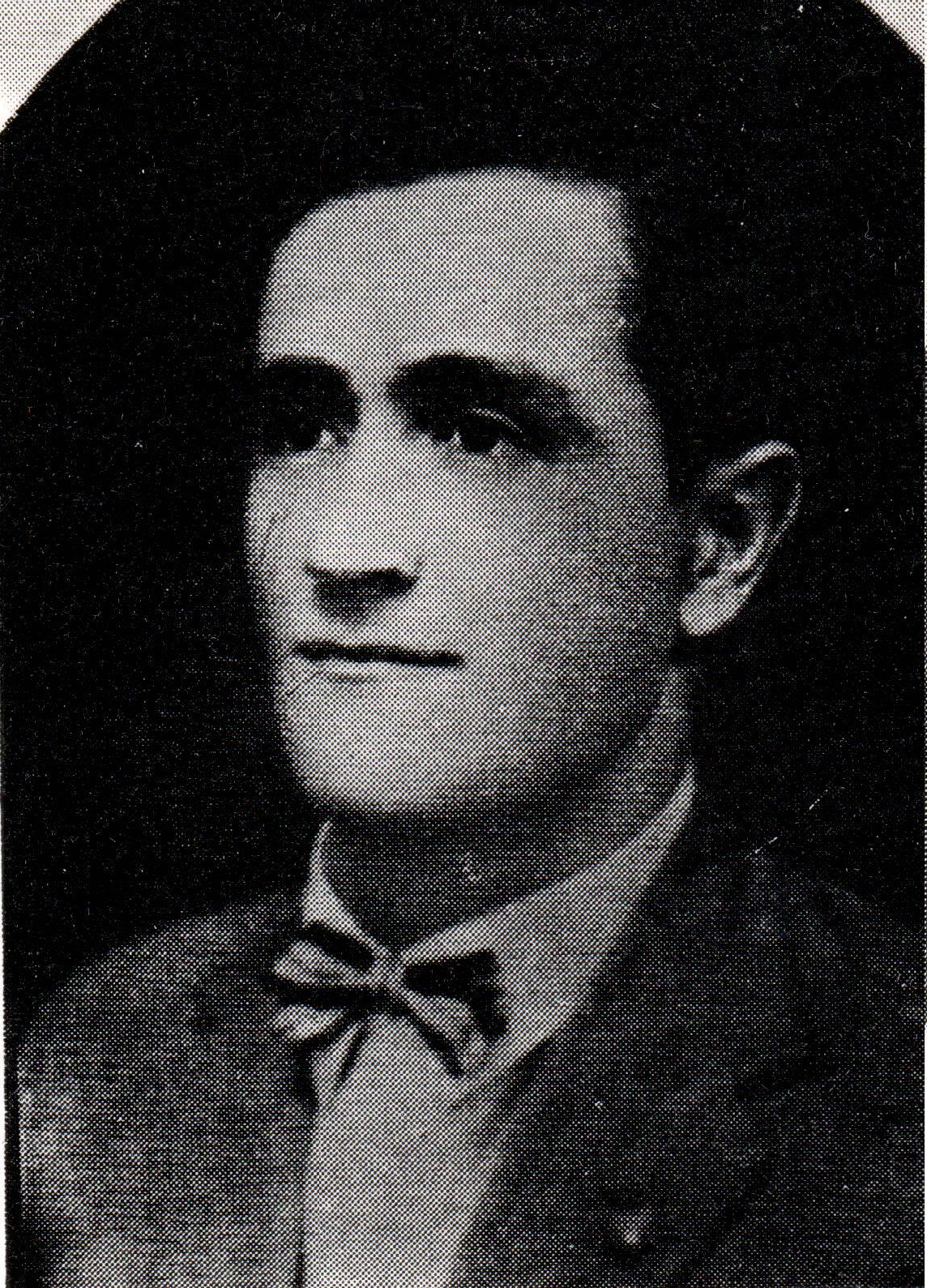

Života S. NEIMAROVIĆ

ŽIVOTA NEIMAREVIĆ*, son of SAVA; born on November 8, 1920, in Mostar. Tailor by trade. His father Sava was a well-known pre-war communist and revolutionary. Života became a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) in 1939 and served as the secretary of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia for Nevesinje from 1941 to 1942. He was one of the first fighters, part of the initial group of volunteers consisting of 28 Mostar communists, who went to the eastern Herzegovina region in the summer of 1941 to work on uprising activities. Leading the group was Savo Medan. Equipped with 16 rifles, 150 rounds of ammunition per rifle, a revolver, and at least two “kragujevka” rifles, Života and Gojko Samardžić, both tailors, sewed slippers made of bovine leather for all the volunteers, allowing them to move silently through the city to join the detachment. Života was sent to the Nevesinje region to organize the partisan army. He served as the deputy political commissar in the headquarters of the First Battalion. He was captured by the Chetniks “during the withdrawal of partisan forces from Herzegovina and handed over to the Italians.” He was executed on July 28, 1942, near Bileća.

After Života’s death, an Italian record was found. Carabinieri commander Giuseppe Falcone, who reported from Bileća to the command in Dubrovnik, stated that on July 28, 1942, “at 5 o’clock, a squad of voluntary anti-communist militia from Bileća carried out the death penalty on the communist Života Neimarević, the son of the late Sava and Anika Andelopolj,” who was shot in Mostar and was 21 years old. The report mentioned that he was previously captured and wounded in the Bileća area, and it stated: “The punishment was carried out near the Orthodox cemetery. Before the execution, the condemned refused to have a blindfold placed over his eyes and requested to speak. When allowed to do so, he declared his innocence. As soon as the squad commander ordered the firing, Neimarević shouted: ‘Long live the Communist Party of Yugoslavia!'”

Excerpts from literature:

After Života joined the detachment, his family (grandmother Cvijeta, mother Anika, brother Todor, sister Ksenija, and brother Pavle) left for Serbia, as instructed by the Ustasha authorities. “Života was at the rear of the column, overseeing that they took everything. I followed them to say goodbye to Života, but he didn’t allow me to. Instead, he bid me farewell and told me to take care of our mother, brother, sister, and grandmother, who were going to Serbia, as I was now the oldest male in the family. He told me that if things got tough for me in Serbia, I should return and continue working for ‘our cause.’ As they passed by Laza Radišić’s house, where Laza’s daughter Gana and Ljubica Samardžić (now Dević, living in Belgrade) were sitting, Života spoke to Gana and asked her not to tell anyone what they had seen. (…) That was the last time Života saw his family. We didn’t hear anything about him throughout the war. It wasn’t until January 1945 that we learned of his death.”

Života’s brother Pavle, also a member of the Communist Youth League (SKOJ) since 1940 and part of the partisan ranks from 1944, described the first days of the war in Mostar: the brief April War – Života’s efforts to rally the scattered army, collecting abandoned weapons, and distributing food to impoverished families (Pavle Neimarović, “Before the War Task”):

“The first rays of sunlight on April 6, 1941, found me in the garden below the house. From that spot, the Jasenice airport was visible as the palm of my hand. In front of the hangars, the planes glistened in the morning sun. Parades and inspections took place every Sunday, which I enjoyed observing. Suddenly, between 6 and 7 o’clock, a larger group of planes appeared from the southwest, flying low directly above the airport. A tremendous roar followed; explosions echoed one after another. I neither saw nor heard the planes dropping any cargo, as I paid no attention to it. After the explosions, columns of smoke rose over the airport – from the hangars and the planes in front of them. The group of planes flew over the city from south to north, and then more explosions were heard, accompanied by columns of smoke and dust around the coal mine. Some planes separated and headed west, while others returned at a lower altitude above the city, engaging in machine gun fire against the remaining planes on the ground. In Mostar, there were frequent exercises with planes, so we were accustomed to the noise. Initially, I thought it was some kind of exercise, so I didn’t pay much attention to it. However, neighbors started appearing in the gardens, asking me what was causing the thundering noise. Života and Sava Medan ran up and also asked me what was happening. When they saw the smoke at the airport and the mine, and the circling planes unleashing fire, they immediately concluded that it might be an undeclared war. Sava told the neighbors the same, and we all went back to the yard. In the upper courtyard, we met my sister Ksenija, whom Života had ordered to be in front of the church early in the morning, before 6 o’clock, to hear what people would say when they saw the slogans we had written on the church walls overnight. Sava immediately went down the streets to the city, and Života walked along the street towards the army positions, located in Paja Svorcan’s meadow just behind the last houses. I hurried after Života. There was a deployed battery of anti-aircraft guns, and a little higher, in the area east of the Orthodox New Cemetery, on Medan’s meadow, there were anti-aircraft guns… I left the shop, leaving Jovo Pejanović inside, who also worked at Milan’s place. (…) Života asked the soldiers why they weren’t shooting at the enemy planes, whether they didn’t see that it was war and that they had destroyed all the planes at the airport. The soldiers remained silent at first, and then they said they had no orders to open fire and told him to leave. Then a lieutenant arrived, who lived in Vidak Ivelja’s house. When the soldiers told him how Života was urging them to shoot, he started shouting at Života, accusing him of spreading communist propaganda, claiming it wasn’t a war but just exercises because he would have been informed if war had been declared. He ordered Života to leave, as he would be arrested! He soon inquired about it from Dare Ivelja, Vidak’s daughter, who came out to see what was happening, who Života was and what he was, whether he was a communist, saying that he was inciting the soldiers. As Života had already gone home, the lieutenant sent a soldier with a rifle to bring him, but the experienced communist had already taken cover. We went back to the garden. While Života was talking to the neighbors about the war, someone came running and shouted that the radio had reported that Belgrade had been bombed and that the enemy had treacherously attacked us without declaring war. At that moment, a plane flew low from north to south, and we heard the first machine gun fire from the anti-aircraft guns positioned above our houses. It was clear to see the tracer rounds hitting the plane, which shortly thereafter crashed below Čekrk towards the village of Bečevići. We were thrilled by the downing of the enemy plane but saddened by the realization that the war had indeed started. Života and I went back to the soldiers in their positions. The lieutenant spoke sharply over the phone, as if arguing with someone, constantly looking at Života, but no longer threatening or swearing as before. It seems he realized that Života was right and that they were an hour late in opening fire on the enemy planes. During that time, the enemy had achieved a lot, as they had destroyed almost all of our planes.”

Ćemalović, Enver (1986): Mostarski bataljon, Mostar; grupa autora (1961): Hercegovina u NOB 1. dio, Beograd, Vojno delo; grupa autora (1986): Hercegovina u NOB 2. dio, Beograd; Bajić, Nevenka: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije u Hercegovini u ustanku 1941. godine; grupa autora: Spomenica Mostara 1941-1945.

Photo of the memorial plaque: S. Demirović (2018), photo of the fighter: brochure “Partizanski spomenik u Mostaru”

Do you have more information about this fighter? Share your stories and photographs. Let's keep the memory alive!