Stonemasons

Stonemasons

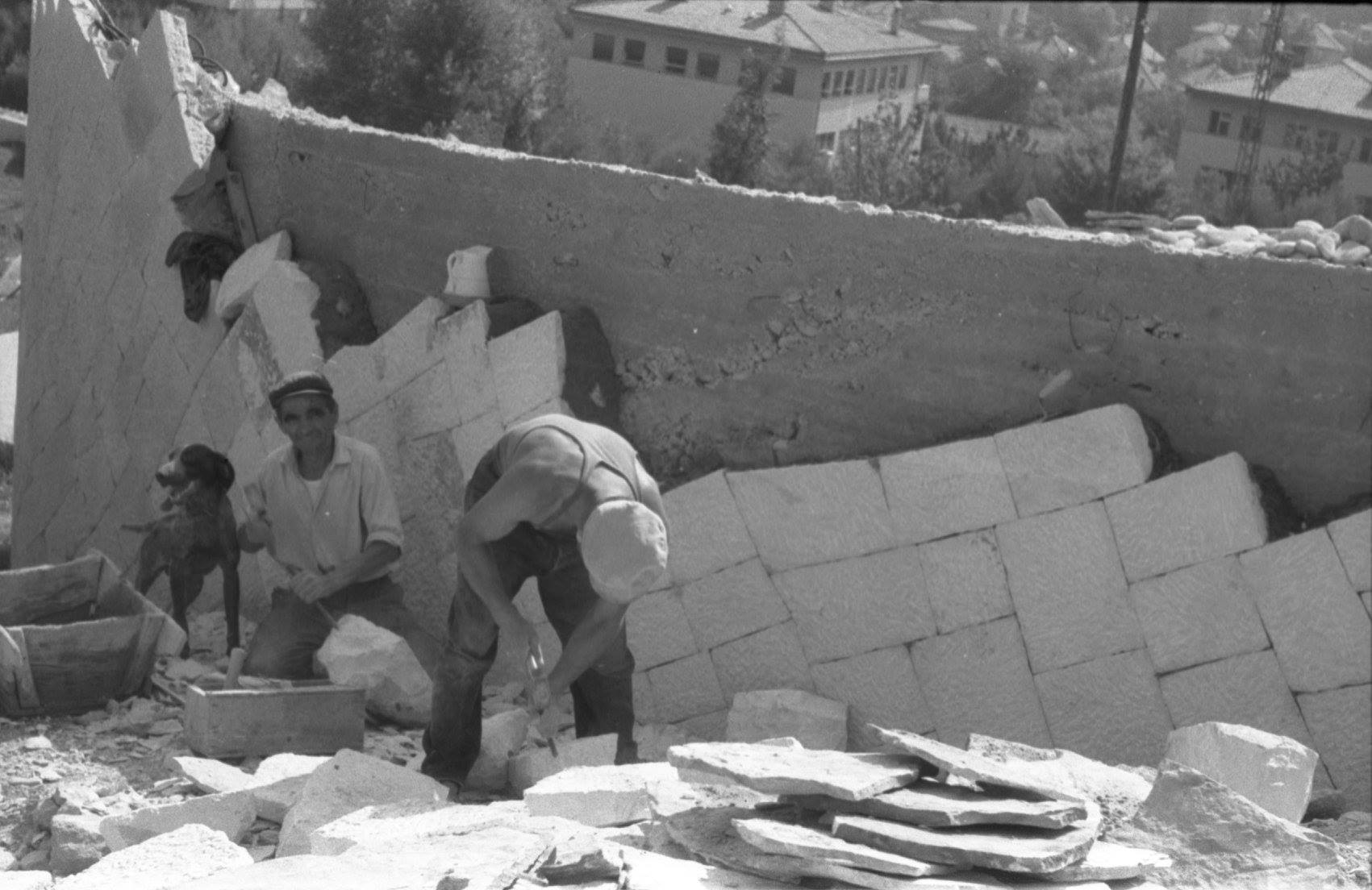

Masons from Posušje

Text content

During the construction of the Partisan Memorial Cemetery, master stone masons from Posušje were involved, in addition to masters from the island of Korčula.

Featuring: Filip Kovač (Mostić), Milan Jukić, Ivan Kovač (Mostić), Ivan Jukić (Itan), Milan Kovač, Slavo Kovač, Branko Penava, Ćipe Penava, all from Posušje. The supervisor of the project was Mijo Mandurić (Đinović). The photographs were provided by Vinko Kovač, the son and grandson of the masters in the photos. Source: CIDOM.

“One night, I decided to go up, to the construction site. From a distance, I could hear a song, the harmony of voices, a choir without words. Step by step, I arrived. I watched from the sidelines, from the darkness: acetylene lamps or perhaps even more ancient carbide lamps (Karbidslampe, Karbidlicht), harsh light and even harsher shadows. And something mysterious was happening in the light. Barba, gray-haired, his hair electrified, scattered in all four directions, acting like a magician, like a spirit emerging from stone. Suddenly, he raises a hammer and chisel (Vorschlaghammer und Meißel), everyone raises their hammers, solemnly silent, and a sudden silence ensues, revealing the voices of the night—crickets, the cry of nocturnal birds, the sound of the Neretva river in the distance. One of the masters, obviously assigned to that role, starts the wordless melody again, mournful and mysterious, like in some stone-worshiping ritual. Barba’s hammer captures the rhythm, strikes the stone block in front of him, and instantly, the synchronized pounding begins. The song clearly harmonizes the rhythm and strength of the strikes. When the melody begins to “rise” (now everyone is singing), the sound of the strikes becomes deafeningly loud… when the “descent” starts, the blows become gentler.

“One night, I decided to go up, to the construction site. From a distance, I could hear a song, the harmony of voices, a choir without words. Step by step, I arrived. I watched from the sidelines, from the darkness: acetylene lamps or perhaps even more ancient carbide lamps (Karbidslampe, Karbidlicht), harsh light and even harsher shadows. And something mysterious was happening in the light. Barba, gray-haired, his hair electrified, scattered in all four directions, acting like a magician, like a spirit emerging from stone. Suddenly, he raises a hammer and chisel (Vorschlaghammer und Meißel), everyone raises their hammers, solemnly silent, and a sudden silence ensues, revealing the voices of the night—crickets, the cry of nocturnal birds, the sound of the Neretva river in the distance. One of the masters, obviously assigned to that role, starts the wordless melody again, mournful and mysterious, like in some stone-worshiping ritual. Barba’s hammer captures the rhythm, strikes the stone block in front of him, and instantly, the synchronized pounding begins. The song clearly harmonizes the rhythm and strength of the strikes. When the melody begins to “rise” (now everyone is singing), the sound of the strikes becomes deafeningly loud… when the “descent” starts, the blows become gentler.

Every stone resounded like a musical instrument. I knew, of course, that different types resonate differently, the softer the stone, the deeper the sound. Paradoxically, and somewhat comically, the hardest granite squeaks, marble sings with a mezzo-soprano, and limestone, the most musical stone, has a beautiful, velvety alto. The stonemasons notice even more. “Each sings its own song,” says one of them, convinced that each block is a separate entity. But when the communal carving begins, the rhythm encompasses every “stone instrument” and suddenly, every hand movement, every body position, so that the whole orchestra acts simultaneously as its own metronome. And when the tool strikes begin to “waver”—a sign that concentration has waned—the Spirit from the stone, Barba, raises the hammer disapprovingly. A signal that work momentarily pauses and the strikes need to be synchronized from the beginning. They wait for the delicate voice of the first singer and Barba’s first strike… “Why does the song have no words?” I asked once. The answers were simple and convincing: “It doesn’t have them, there never were any!” Or: “That’s how our forefathers sang it!”

Have additional information on stonemasons from Korčula, Posušje, Dubrovnik or other areas?

Please share your photos and memories.

“What do the master stonemasons who carve and build a city beyond time and space look like? My friends from Mostar sought them out on Korčula and rallied everyone in their village who knew how to hold a chisel and hammer. They brought them somewhere in the late fifties or at the very beginning of the sixties. They were modest, kind, and pleasant, and they carried out their work devoutly, almost liturgically: their ringing, choral liturgy of carving lasted with minor interruptions for a full five years.

“What do the master stonemasons who carve and build a city beyond time and space look like? My friends from Mostar sought them out on Korčula and rallied everyone in their village who knew how to hold a chisel and hammer. They brought them somewhere in the late fifties or at the very beginning of the sixties. They were modest, kind, and pleasant, and they carried out their work devoutly, almost liturgically: their ringing, choral liturgy of carving lasted with minor interruptions for a full five years.

Barba, which also means uncle and grandfather in the local dialect, led them—the patriarchal chief of the group, the caretaker, the one who would report to parents and fiancées what everyone did and how they did it when they returned to their island. As soon as he arrived, Barba chose the location for the “carving workshop,” and when the canopy was raised, he designated a spot for his workbench, which resembled both a lectern and a pulpit. Then he ordered that the trunk made of planks (Bohle), but without a lid or bottom, be filled with sand and small stone debris so that the piece to be carved would rest softly and not be damaged during work. Facing his lectern, the masters arranged their own, slightly smaller trunks.

Due to the heat of Herzegovina, they worked more at night than during the day—from dawn until after breakfast and from sunset until midnight. Mostar, that wonderful, now former city, had the established habit of eagerly awaiting the midnight refreshment that flowed from the Neretva riverbed during the summer months. Sometimes it seemed that everyone, even the children, had completely forgotten that one could sleep a little at night. I adopted their custom not only because I also needed the anticipation of freshness for a good sleep and the overall rhythm of work the next day but also because I was playful, or rather nervous, and somewhat frightened. I had promised the citizens of Mostar that I would create something unprecedented for them, burdened them with costs, set in motion extensive works, but was I really certain that I would see it through to the end, just as I had conceived?”

The text was published in the Mostar information magazine MM, in issues 12/13, in June 1997.

Stonemasons from Korčula

From Lumbarda:

- Ante Jurjević „Antunica“,

- Nikola (Miko) Lipanović „Balaun“,

- Stjepan Jurjević „Skorin“,

- Ilija Šestanović „Kristić“

- Stjepan Šestanović „Kristić-Siromah“,

- Ante Kriletić „Barbare“,

- Ive Lozica „Zane“,

- Ante Milina „Lave“,

- Stanko Mušić „Crnej“,

- Ante Mušić „Tuci“.

From Žrnov:

- Berislav (Bere) Curać „Goga“,

- Jure Curać „Goga“,

- Jakov Curać „Skajko“,

- Ante Brčić „Abel“.

From the islet of Vrnik (Škoj):

- Jure Kučija „Marinice“,

- Mauro Fabris,

- Vinko (Braco) Fabris „Škojar“

- Vinko Dragojević

- Ivo Biočin

Great renovation of 2018

Some new stonemasons and diligent hands, partly manually and partly with the help of technology, made new memorial plaques during the major restoration in 2018. Most of these memorial plaques were destroyed during the deliberate attacks in the summer of 2022.

Our thanks to S. Špago for providing the photographs.

Here you can see pictures from the 2018 renovation.

The following participated in the 2018 restauration:

– JP Parkovi worked on the landscaping of green areas and the monument’s surroundings.

– “Građevinar Fajić” was responsible for the reconstruction of the monument itself, including the stone ornaments.

– The company “Dema & S“, specialized in electrical installations, and has installed the lighting, video surveillance, and other necessary electrical installations (at least some of it is no longer in function).