brochure "Partizanski spomenik u Mostaru" (1980)

book “Spomenica Mostara 1941-1945.”

another document or proof of the memorial stone (e.g., a photograph).

Alija A. RIZIKALO

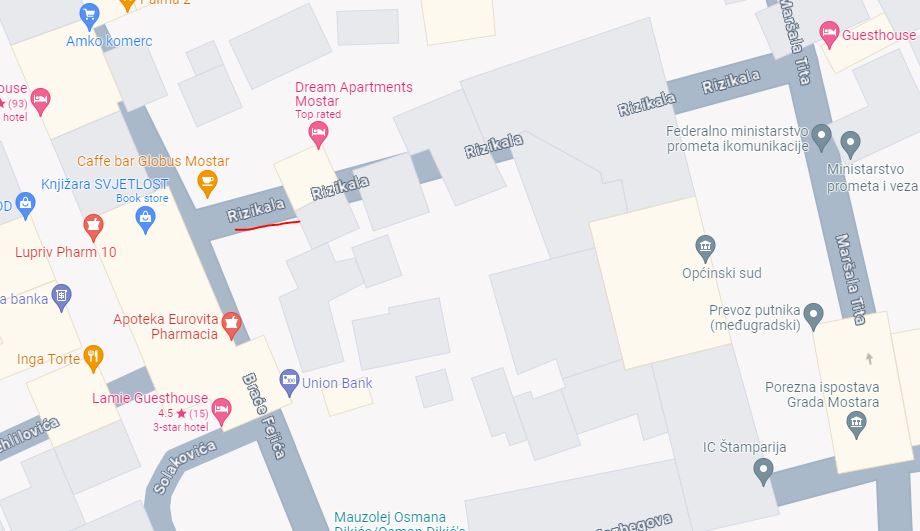

ALIJA ALICA RIZIKALO, son of ALIJA, born on September 15, 1923* in Mostar, carpenter, member of the League of Communist Youth (SKOJ) since 1941 and member of the Local Committee of SKOJ since 1943. In the Battalion since July 1943, fighter of the Mostar Youth Detachment, captured after two months of joining the detachment in Kamena near Mostar. Publicly hanged together with Drago Palavestra in Mostar on July 15, 1943, at Musala Square, in the park next to Hotel Neretva. Posters of the SS section commander were plastered throughout the city streets: “Sentenced to death by the Summary Court in Mostar: Drago Palavestra, student, 18 years old, from Mostar; Alija Rizikalo, carpenter, 19 years old, single, from Mostar. Palavestra worked as a gatherer for the partisans. Under the pretext of false facts, he lured his schoolmates to the outskirts of Mostar in the evening hours, where they were regularly attacked by partisans and taken away… Rizikalo did not respond to the call of the Croatian army and became a military deserter, joining the partisans.” Both bravely shouted before their death: “Long live the Communist Party of Yugoslavia,” “Long live Comrade Tito,” “Long live the Soviet Union.” In an article, it was stated that, by order of the authorities, the bodies were left there until 11 p.m. on July 25, 1943. A group of SKOJ members was preparing to abduct the hanged comrades, but the bodies were continuously guarded. A Memorial Monument was erected at the site of their death after the war. Also, a street in Mostar is named after Alija Rizikalo.

Mother Hana Rizikalo, born Kalajdžić, was described as a “true partisan mother” to the illegal fighters and couriers who came to her: “She loved them like her own sons, washed their laundry, patched their clothes, and bid them farewell with a cheerful look and care.” She had her own “conspiracy system,” hiding weapons and materials in various holes and in the toilet. When she accompanied her son to the detachment, she told him: “My son, do not shame me. It’s better for you there than among these bandits. Go, my son, and may luck be with you.” On the day of Alija’s hanging, she sent a message to her tenant, the illegal fighter Džemil “Džemo” Šarac, whom she knew only under his illegal name: “Vlado, my son, run away, see they killed my Alija. Run, they will catch you.” Alica’s uncle, Mustafa Kalajdžić, entering his sister Hana’s house, shouted: “Hana, be happy! Alija is the first martyr in our neighborhood!”

According to the archives of Radmilo Braca Andrić, the remains of Alija Rizikalo were transferred and buried in the Partisan Memorial Cemetery in Mostar.

EXCERPTS FROM LITERATURE:

Revolutionary Avdo Humo recalled his encounter with Alija Rizikalo during his stay in war-torn Mostar:

“I went down into the yard. Moonlight, white and warm, illuminated the yard and chased away the shadows of the high walls surrounding the house. It was a true, warm summer night in Mostar, filled with a mysterious restlessness. One young man was sitting on a chair by the door, while another was walking around the yard. I approached the walker and asked him his name. He said: Alija Rizikalo. I could see on his face that he was uneasy, so I asked him what was wrong. ‘I didn’t tell my family that I won’t come home tonight. I’m afraid my mother will be worried. But my comrades told me I can’t leave the house until tomorrow. I could still sneak out now. There are only Italian guards on the street,’ he said softly. ‘Don’t take risks. You shouldn’t jeopardize yourself for such things. It’s possible that you’ll be caught,’ I comforted him. He remained silent. I put my hand on his shoulder, and the two of us continued walking in the yard. He talked about how he brought three rifles tonight. He was in the Cernica district. ‘A female comrade brought the rifles hidden under the embers. I was thinking about how to transport them. At first, I thought of cutting the grass in the garden, putting the rifles in a bag, covering them with grass, and then carrying them across the Neretva River on some cart. But I couldn’t find a cart in the neighborhood. So, I decided to swim across the Neretva with that bag containing the grass and rifles. It was a struggle for me to bring the bag to the river. It was heavy. And when night fell, I took off my clothes, wrapped them around my head, placed the bag in front of me, and started swimming, pushing it. I swam with difficulty, the bag was heavy, and I felt like it would sink at any moment. But I held onto it tightly. The river’s current carried me further than I had planned. I barely managed to pull myself out. The bag was as heavy as lead. I got dressed and lay down on the warm sand to rest for a bit. I was so tired that I felt sleepy. I quickly got up and took the bag, but I immediately realized that I wouldn’t be able to carry it to Brankovac. What should I do now? I was told that the rifles had to be in Vasko’s house before curfew. I had no other choice but to remove the wet grass from the bag, squeeze it well, wrap the rifles with it, and head towards Brankovac, whatever happens. And that was difficult for me. On the way, I encountered some people, even an Italian patrol. No one paid attention to what I was carrying on my shoulder. I looked at the face illuminated by the moonlight. Well, he’s just a boy, I thought. ‘You’re a brave young man, you have a heroic heart,’ I said, squeezing his shoulder. ‘It’s nothing! Any young person in Mostar would do the same. I just feel sorry that my mother will worry about me.’ And suddenly he asked me, ‘Can I go home? I’ll come back tomorrow.’ ‘The order is that you can’t, you have to respect it,’ I responded hesitantly. If he had insisted a bit more, I would have let him go. Like a child, he was concerned about his mother, and he could have been killed carrying those rifles and never see her again. We remained silent and kept walking. (…)”

Later, when the gunshots were heard, Alija volunteered to go and check what was happening:

“… Rizikalo asked, ‘Should I go and find out what’s going on?’ Sava angrily replied, ‘What can you find out? You could get killed.’ ‘He could go, Sava. It’s good that we know what’s happening. Just let him leave the revolver with us. It’s better if he goes without it; he’ll have an easier time if he happens to get caught,’ I said to Sava. Rizikalo happily took out the revolver from his pocket and rushed off. It hadn’t been ten minutes since he left when suddenly everything fell silent. We felt a sense of relief due to the quietness, as if the atmosphere had been filled with warm May air. I looked at my watch. It was only half past eleven. I certainly hadn’t slept for even half an hour. We relieved the guard at the door and waited a little longer to see what would happen. I could sense that the neighbors were expecting the same. Someone let the water flow from the faucet again. The sound of drops hitting the basin had a calming effect. We could also hear the crickets, which hadn’t been audible amidst the noise in Mostar. ‘Let’s go to sleep; there’s no point in standing here!’ someone said. The group started dispersing. I told Sava that I would wait for Rizikalo. After an hour, someone knocked on the door with the prearranged signal, softly at first and then louder. It was the Skojevac! I asked him what had happened. ‘I don’t know. The gunfire quickly subsided. I didn’t meet anyone except an Italian patrol, so I hid in an alley,’ he replied. ‘Did you see your mother?’ I asked him. ‘Yes,’ he answered shyly. ‘Go to sleep,’ I told him. I lay down and contemplated. What tenderness is woven into the bravery of this young man. This fragile boy’s body carried great human virtues within, which moments in history like these ignite, turning ordinary people into heroes. I fell asleep with these thoughts.”

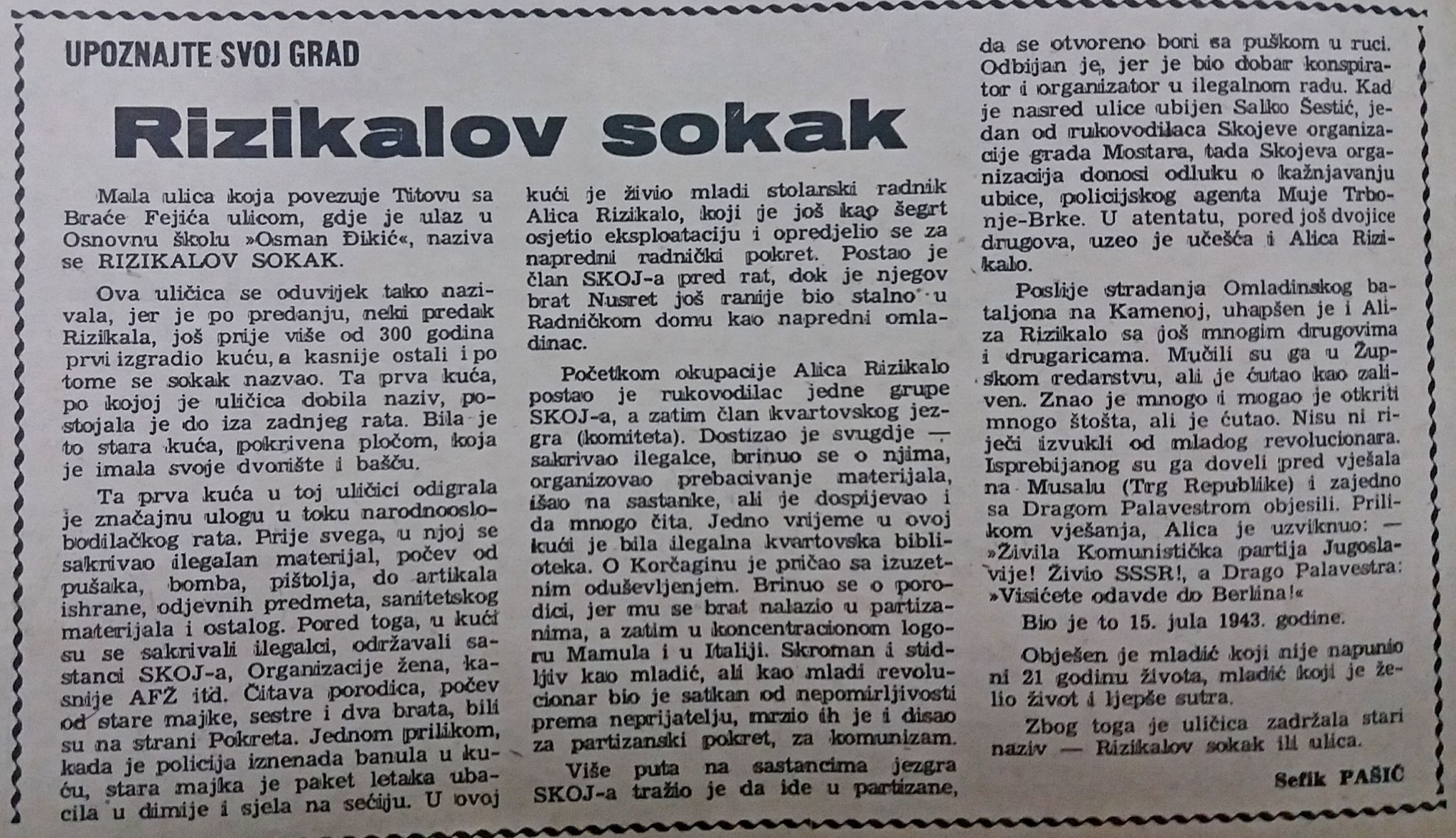

In one article, the role of the entire Rizikalo family is emphasized, particularly Alija’s role.

“The first house (Rizikalo’s) in that little street played a significant role during the People’s Liberation War. First and foremost, it served as a hiding place for illegal materials, ranging from rifles, bombs, and pistols to food supplies, clothing, medical supplies, and more. In addition to that, the house provided shelter for illegal activists, served as a meeting place for SKOJ (League of Communist Youth) members, Women’s Organization, later AFŽ (Antifascist Front of Women), and others. The entire family, from the elderly mother to the sisters and two brothers, were on the side of the movement. On one occasion, when the police suddenly burst into the house, the elderly mother put a bundle of leaflets into her baggy trousers and sat on the armchair. In this house lived the young carpenter Alica Rizikalo, who, even as an apprentice, experienced exploitation and chose to join the progressive workers’ movement. He became a member of SKOJ before the war, while his brother Nusret had been actively involved in the Workers’ Club as a progressive youth. At the beginning of the occupation, Alica Rizikalo became the leader of a SKOJ group and later a member of the neighborhood core (committee). He did it all—hiding illegal activists, taking care of them, organizing the transfer of materials, attending meetings, and managed to do a lot of reading. For a while, this house served as an illegal neighborhood library. He spoke with exceptional enthusiasm about Korčagin. He cared for his family, as his brother was with the partisans, and later in the concentration camp Mamula and in Italy. Modest and shy as a young man, but as a young revolutionary, he was driven by an irreconcilable spirit towards the enemy; he hated them and breathed for the partisan movement, for communism. Several times at SKOJ core meetings, he requested to join the partisans and openly fight with a rifle in his hand. His request was denied because he was an excellent conspirator and organizer in clandestine work. When Salko Šestić, one of the leaders of the Skoj organization in Mostar, was killed in the middle of the street, the Skoj organization decided to punish the murderer, police agent Mujo Trbonja-Brko. Alica Rizikalo participated in the assassination, alongside two other comrades. After the tragedy of the Youth Battalion at Kamena, Alica Rizikalo was arrested along with many other comrades. They tortured him at the Župsko police station, but he remained silent as a stone. He knew a lot and could have revealed many things, but he stayed silent. They couldn’t extract a single word from the young revolutionary. They brought him beaten to the gallows at Musala Square, where he was hanged together with Drago Palavestra. During the hanging, Alica shouted, ‘Long live the Communist Party of Yugoslavia! Long live the USSR!’ and Drago Palavestra said, ‘I wish you all hang from here to Berlin.’ It was July 15, 1943. A young man who hadn’t even turned 21 yet, a young man who wanted life and a better tomorrow, was hanged.”

*According to the book “Spomenica Mostara 1941-1945”.

Ćemalović, Enver (1986): Mostarski bataljon, Mostar; http://mosheristorija.blogspot.com/2015/02/oni-su-pobijedili-smrt.html; Konjhodžić, Mahmud (1981): “Mostarke”: fragmenti o revolucionarnoj djelatnosti i patriotskoj opredjeljenosti žena Mostara, o njihovoj borbi za slobodu i socijalizam, Opštinski odbor SUBNOR-a Mostar; Hercegovina u NOB 2. dio, Beograd; Seferović, Mensur: Mostarski kolopleti, edicija “Mostar u borbi za slobodu”, knjiga 8, Mostar; grupa autora: Spomenica Mostara 1941-1945.

Photo of the memorial plaque: S. Demirović (2018).

Do you have more information about this fighter? Share your stories and photographs. Let's keep the memory alive!