Bogdan Bogdanović

Bogdan Bogdanović

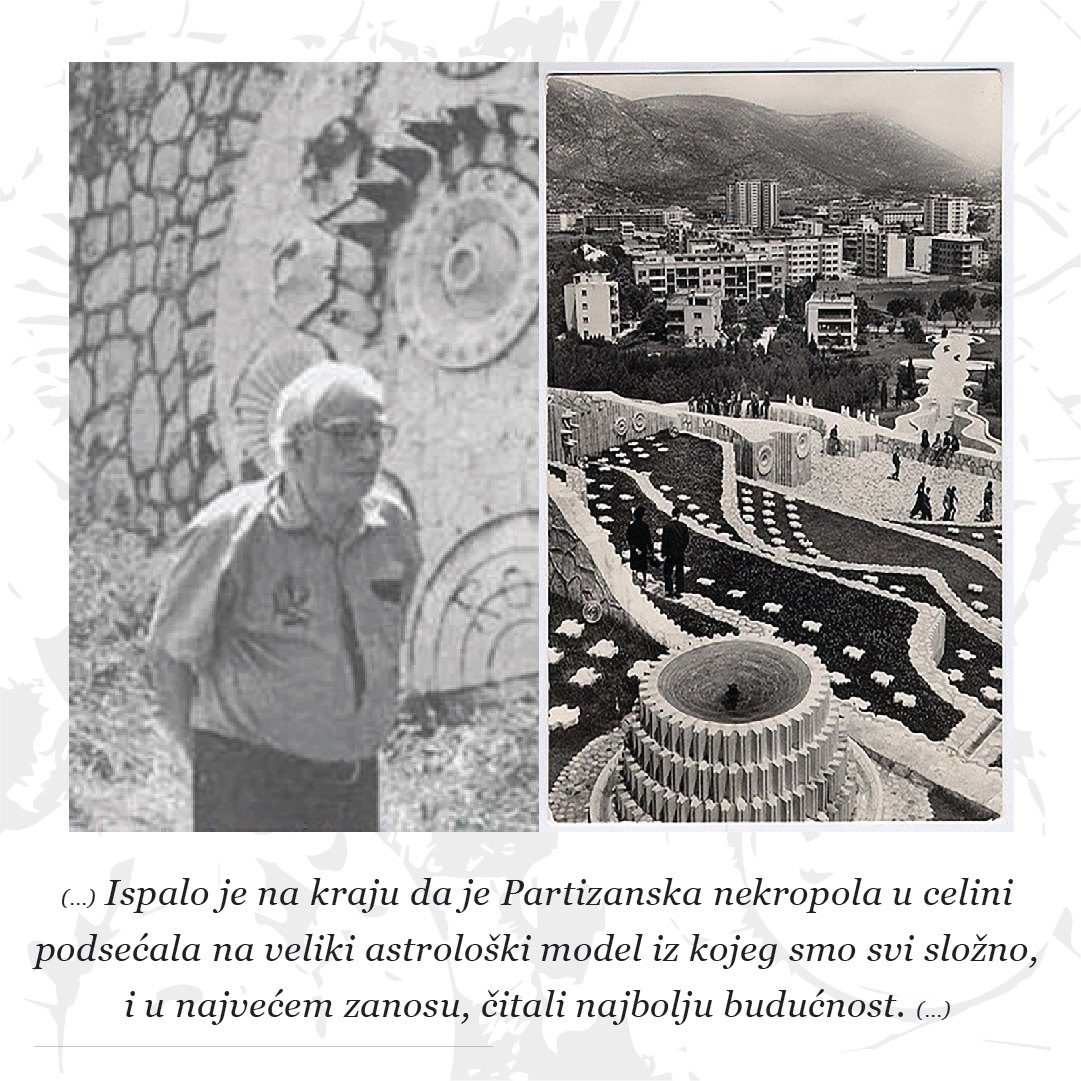

Born in Belgrade in 1922, he too participated in the wartime efforts from 1944. An architect and visionary, he designed over 20 monuments to the victims of fascism. Among the most famous are The Stone Flower in Jasenovac and the Partisan Memorial Cemetery in Mostar.

Read Bogdan’s biography and timeline (in Serbian/Bosnian/ Croatian).

Review the collection of Bogdan’s drawings at the MoMA museum in New York.

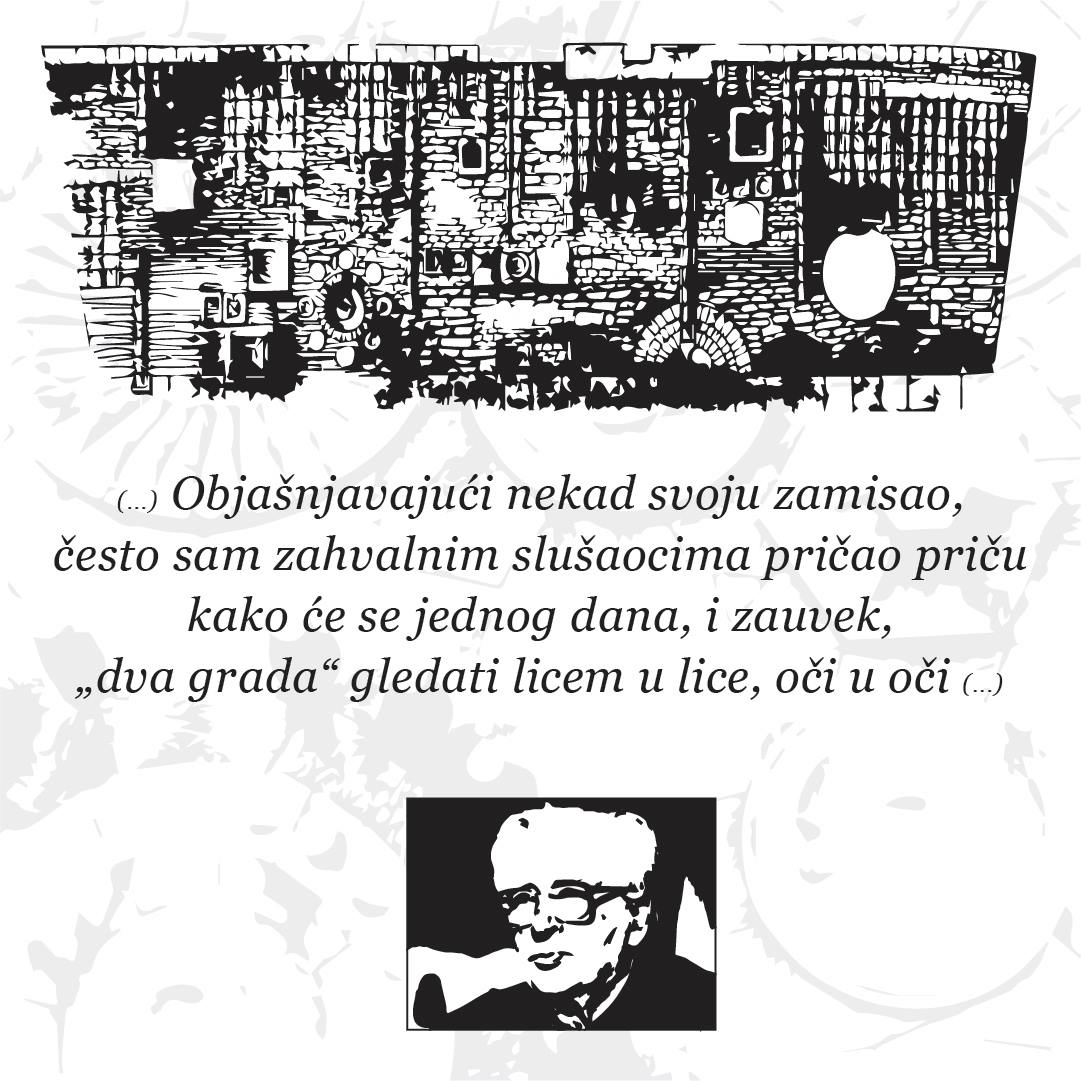

(…) I often told the grateful listeners the story of how one day, and forever, the “two cities” will look face to face, eye to eye – the city of dead anti-fascist heroes, mostly young men and women – fighters and the city of the living, for which they laid down their lives…

Bogdan 1997.

In Bogdan’s words:

“Building the Mostar acronecropolis, I was carried by some deep, inner fire. It was not a simple and easy job, yet I did it without nausea and fatigue and, in fact, I was seized by some new understanding of life and death. It may be absurd to say, but as if I hoped to give some of my secret joy to my “new friends”, whose names – Muslim, Serbian, Croatian – just began to line up on the terraces of the necropolis. Their small afterlife city, as I promised to the families, looked into the very heart of old Mostar and the now destroyed bridge of the master architect Hajrudin, once the most beautiful and bravest bridge in the world, a divine construction static, in front of which little Bogdan was tiny as in front of a supernatural phenomenon.”

Bogdan wrote about the Partisan Memorial Cemetery twice. Read about his original idea when he was building the Partisan Memorial Cemetery, and his impressions when he saw it again after the 1990s war.

Bogdan’s Letter from 1969.

The builder who builds in Mostar is burdened with considerations. Mostar is, as is known, one of the most beautiful and unique cities that man has built in this part of the world. On the canyon of the river, with a miraculous bridge after which it was named, stands this special urban structure woven from stone and sun, greenery and water. Of a special, self-similar character, but also of its own soul and will, Mostar is a city of personality, and therefore – the first obligation of the builder is not to betray that personality. How difficult it is to build in this city, how many possible detours, how many opportunities for the imagined not to be brought to an end, or if it is brought wrongly, hastily, so that the builder feels guilty!

The builder of the Mostar Monument built it with genuine fear. But, from fear sometimes courage and audacity are born. So, here is another statement from the builder: If he can say for any of his constructions that they were built in high temperatures, he certainly can say that for the Partisan monument in Mostar. So if any of the visitors and friends of this monument sense that temperature, it will be a great reward for the builder.

The monument in Mostar is, in short, a monument of a city. It primarily tells us about Mostar – the fighter, about Mostar – the poet. The monument can sometimes speak of the spiritual and physical beauty of the city, to be inspired by it. Recent history has shown that Mostar – the city, was a city – a man, a fighter, the same thought. The patriotic and humanistic solidarity of this city in the revolution is legendary, and above all, it is true.

Mostar – this city-human could not understand the revolution differently than as an embodiment of the principles of life, or as a picture of the future. So, if it is said that the Monument in question expresses faith in life, then this pays tribute to the special, complex and at the same time simple philosophy of the human of Mostar, and the human of Herzegovina. This is primarily an unwavering faith in life. Lives were extinguished in the name of life, in the name of light and sun, the eyes of young men and women were closed. But, even closed, they remained open. I learned this thought every day, followed it while building this Monument. (The builder could learn a thing or two while working on his construction.)

Otherwise, this builder has established, from the first sketches, an idea that persistently held him until the end – this should be a monument that can see. It is less important whether we see it ourselves and how we see it, although it imposes itself on the view with its physics – it is more important how it looks at us and sees us! Once I almost accidentally said that the Monument is so positioned that the fighters of the revolution look at their city from it. For the people, this remained as a kind of irrefutable explanation. Maybe there is some truth in this slogan.

If Mitrovica, Prilep, Kruševac, Jasenovac are monuments in the landscape, indivisible from the sun, fog, water, grass – this is a monument of urban landscape and space. The monument and the city look each other in the eye. The hill opened, it was encrusted with stone interweavings and old plates taken from dilapidated roofs. The smoked plate from Mostar houses, which covered so many troubles and joys, was sanctified, it gained the right to be a symbol, the right to eternity. These plates intertwine and overtake each other with other, richer, bolder stone patterns, a mute but sonorous letter of ornament is written, as it used to be the case of old Mostar buildings. Finally, if some signs had to be carved into this silent and resonant texture of stone and ornament, they had to be, without hesitation, signs of the sun, moon, and stars. Cosmic symbols open before us strange expanses towards which man has always strived, sought himself in them, constantly moved towards them the boundaries of his enthusiasm and knowledge.

And so this turned out to be, at least at first glance – paradoxical. This Monument, which carries the dead within it, is cheerful and exuberant. A person descends down its ramps, returns to the city with faith in the values of life, carried away by the eternal and final aspirations of human strivings. Wasn’t the guiding idea of the youth who gave their lives – just that faith in the strength of human feelings and human mind? The builder of the Monument would very much like every visitor to descend into the city with a feeling of encouragement.

This builder does not need to talk much about his work. If the work itself does not speak, the builder’s words are in vain. Works stand, builders leave. How will generations after us interpret this building? What will they see in it, what will be experienced? Will it tell them anything? Will visitors and the building converse, as it seems, they are already starting to converse a bit?

Many associations are possible, various imaginings. Will our children’s children see in this monument the image of a strange proud and humane city, raised like a mirage somewhere between heaven and earth? And will they recognize their city in it in a distant, proud and difficult time when it was hardest of all to be and remain a human? Not without a certain fear, but also without decisiveness, the builder would briefly answer: they will recognize both the city and the man, they will meet as long as there are man and city.

Bogdan BOGDANOVIĆ

source: “Partizanski spomenik u Mostaru”, IKRO Prva književna komuna, Mostar 1980, pp. 36-38.

Photos: S. Špago.

Bogdan’s Letter from 1997.

Many of the memorial buildings to which I dedicated my best mental and physical strength, today no longer exist or are, at least as things stand now, condemned to unnoticed physical degradation and disappearance. I would feel miserable indeed if I allowed myself to regret, even for a moment, for example, for the most lavish work of my building youth – the Partisan Monument in Mostar, today when there is no longer the real, old Mostar, nor many old Mostar families, whose children rested in this honorable warrior cemetery. Explaining my idea once, I often told the grateful listeners the story of how one day, and forever, “two cities” will look face to face, eye to eye – the city of dead anti-fascist heroes, mostly young men and women – warriors and the city of the living, for which they laid down their lives…

The stone allegory of two cities did not find itself quite by chance, and without any external stimuli, on one of the gray, stone hills of western Mostar. The initial formulas were probably offered to me by what I was reading at the time. Namely, quite vaguely, somewhere between earth and sky – at least so say the ancient books – hovers the city of Hurqualya, the Sufi counterpart of the Manichean Terrae lucidae, which in gnostic speculations represented a kind of starting station for setting off into the world of beautiful, naive, but eternal philosophical and cosmo-poetic images. And I believed that the fallen anti-fascist fighters of Mostar, practically still boys and girls, had at least symbolically, the right to the beauty of dreams. During the period when the monument was being built, therefore in a largely peaceful, calm, bureaucratic, and even insensitive mental and moral environment, from a time perspective of about twenty years, the purity of their motives and boundless, naive self-sacrifice could only remind of the tragic children’s crusades (Kinderkreuzzuge).

Unlike the work on Jasenovac, which for many reasons was very painful for me, trips to Mostar transported me to a completely different world of poetry and reality. Memories of a former extermination camp (Vernichtungslager), no matter how much I ran away from them, often turned into a state of prolonged, barely bearable stress.

On the contrary, building the Mostar acronecropolis, I was carried away by some deep, inner fire. I did this, not exactly simple and easy job, without nausea and fatigue and, in fact, seized by some new understanding of life and death for me. It may be absurd to say, but as if I hoped to give some of my secret joy to my “new friends”, whose names – Muslim, Serbian, Croatian – were just beginning to line up on the terraces of the necropolis. Their small afterlife city, as I promised the families, looked into the very heart of old Mostar and into the now destroyed bridge of the master architect Hajrudin, that once most beautiful and bravest bridge in the world, the work of divine building statics, before which little Bogdan was tiny as before a supernatural phenomenon.

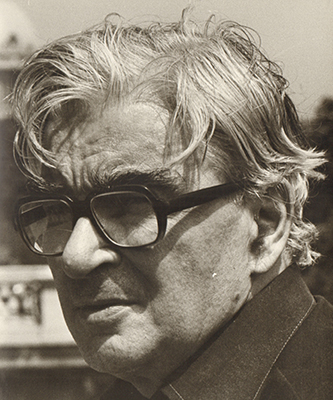

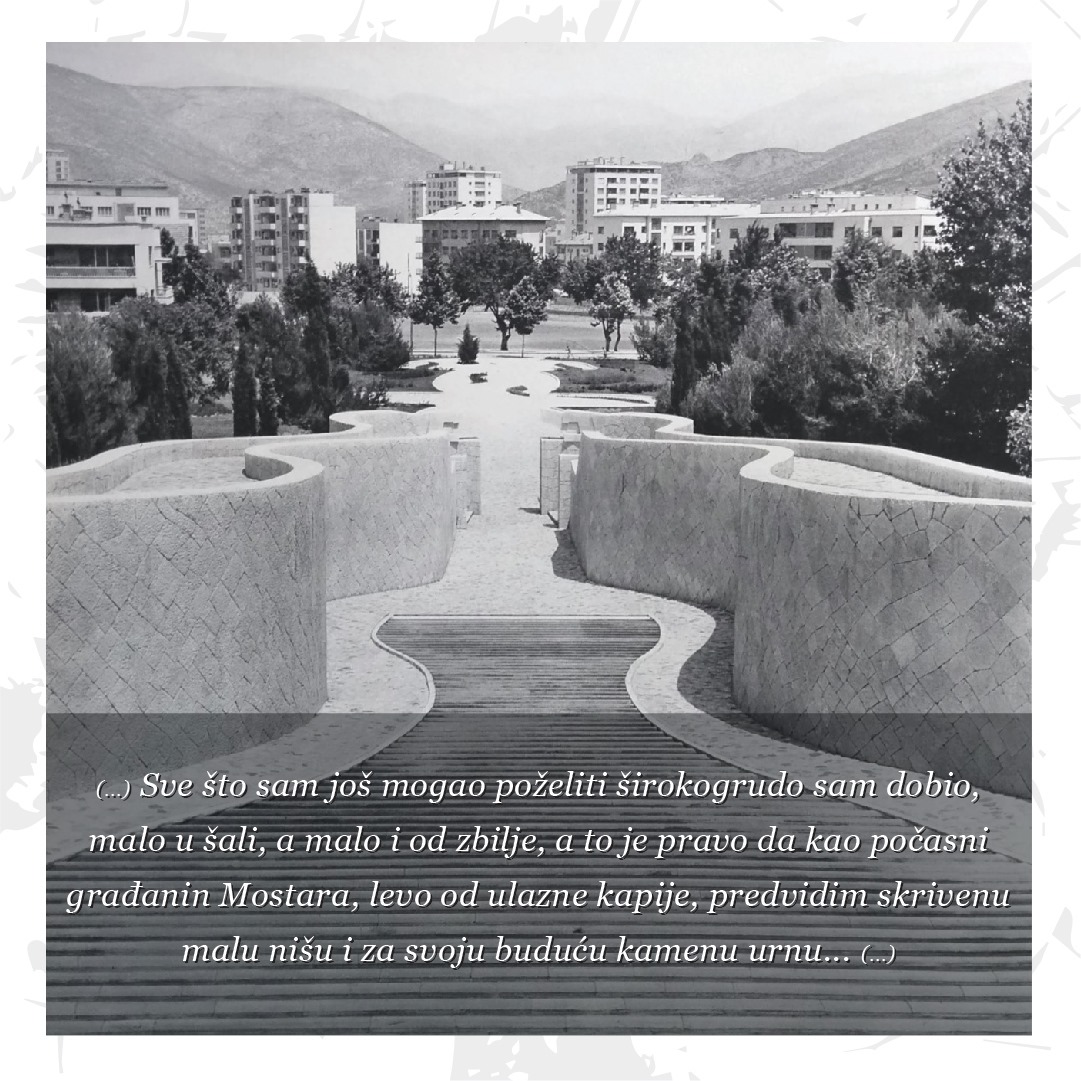

The Partisan necropolis was Mostar in miniature, a replica of the city on the Neretva, its ideal diagram. However, this ideogram of the city, this hieroglyph, this stone sign was not of insignificant dimensions. It reached the outlines of some of the more modest, pre-Balkan, Hellenic acropolises. From the entrance, the lower gate to the fountain at the top (Quelle, Brunnen) it was necessary to overcome twenty and something meters of altitude difference and, winding, stone serpentines walk uphill a good three hundred meters. The way up was shown by the water that flowed over the ringing organs towards the visitor.

What do master stonecutters look like who carve and build a city out of time and space? My friends from Mostar looked for them on Korčula and raised everyone in their village who knew how to hold a chisel and a bat in their hand. They brought them somewhere at the end of the fifties or at the very beginning of the sixties. They were modest, kind and pleasant, and they did their job devoutly, almost liturgically: their ringing, choral liturgy of carving lasted with minor interruptions for a full five years.

They were led by Barba, which in dialect means both uncle and grandfather, the patriarchal head of the family, the guardian, the one who will, when they return to their island, report to parents and fiancées what everyone did and how they did it. As soon as he arrived, Barba chose a place for the “stonecutter’s workshop”, and when the canopy was erected, he determined the place for his desk, which looked like both a cathedral and a pulpit. He then ordered that this box of talpi (Bohle), but without a lid and without a bottom, be filled with sand and small pieces of stone, so that the piece for carving would fit softly and would not be damaged during work. Opposite his cathedral, facing it, the masters arranged their, albeit slightly smaller boxes.

They worked, because of the Herzegovinian heat, more at night than during the day – from dawn to after breakfast and from sunset to midnight. Mostar, that wonderful, now former city, had a settled habit in the summer months to wait on the streets for midnight refreshment coming from the Neretva riverbed. It sometimes seemed that everyone, even the children, had completely forgotten that you can sleep a little at night. I accepted their custom not only because waiting for freshness was also necessary for me for a good sleep and the overall rhythm of work the next day, but also because I was playful, better to say nervous, and a little scared. I promised the citizens of Mostar that I would create something unseen, put them into costs, started huge works, but was I really sure that I would be able to carry everything out to the end, just as I had conceived?

A little bewildered and scattered, I crossed over Hajrudin’s bridge from one bank to the other of the river canyon several times in a row. Sometimes it seemed to me that I was seeking advice from my great predecessor for various difficulties that always unexpectedly arise in working with stone. I felt the stone handrails and profiles and found under my fingers much of what the sense of sight overlooked during the day carelessly. I found in the dark the joints of the blocks, long calcified, felt the metal leeches (Klammer, Klampe) and tension rods (Spanriegel), which stopped the spraying in time and defended the old building from falling apart.

One night I decided to go up, to the construction site. From a distance, a song was heard, a harmony of voices, a choir without words. Step by step, I arrived. I watched from the sidelines, from the dark: acetylene lamps or perhaps still last century carbide lamps (Karbidslampe, Karbidlicht), sharp light and even sharper shadows. And in the light, something mysterious was happening. Barba, gray, hair electrified scattered to all four sides of the world, performs like a magician, like a spirit from the stone. Suddenly, he raises a bat and chisel (Vorschlaghammer und MeiBel), everyone raises bats, devoutly silent, a sudden silence ensues that reveals the voices of the night – crickets, the cry of a night bird, the noise of the Neretva from a distance. One of the masters, obviously specifically assigned for that, starts the melody without words again, plaintive and mysterious, as in some ritual of stone worshipers. Barba’s bat catches the rhythm, hits the block in front of him, and in a moment a complex hitting begins. The song obviously harmonizes the rhythm and strength of the blow. When the melody begins to “climb” (now everyone is singing), the sound of the blow becomes deafeningly loud … when the “descent” begins, the blows become softer.

Each stone resonated like a musical instrument. I knew, of course, that different types resonate differently, the deeper the softer the stone. It is paradoxical, and somewhat comical, that the hardest granite squeaks, marble hums with some mezzo-soprano, and limestone, the most musical stone, has a nice, velvety alto. Stonecutters can notice even more. “Each sings its own song” – says one of them, and that with the conviction that each block is a being for itself. But, when the joint carving begins, the rhythm encompasses every “stone instrument” and, suddenly, every movement of the hand, every position of the body, so that the whole orchestra simultaneously acts as its own metronome. And when the blows of the tools start to “trap” – a sign that the concentration has weakened – The Spirit from the stone, Barba, dissatisfied, strictly raises the bat. A sign that work is briefly interrupted and that the blows need to be synchronized from the beginning. They wait for the thin voice of the first singer and Barba’s first blow…

The fact that the melody was wordless led me to think that it was ancient, protohistoric, from the time when on their island, and on the mainland, some other forgotten, pre-Slavic languages were spoken. Civilizations have changed, languages have merged, but man has remained the same…

“Why doesn’t the song have words?” – I asked once. The answers were simple and convincing: “There aren’t any, there never were!” Or: “That’s how our forefathers sang it!”

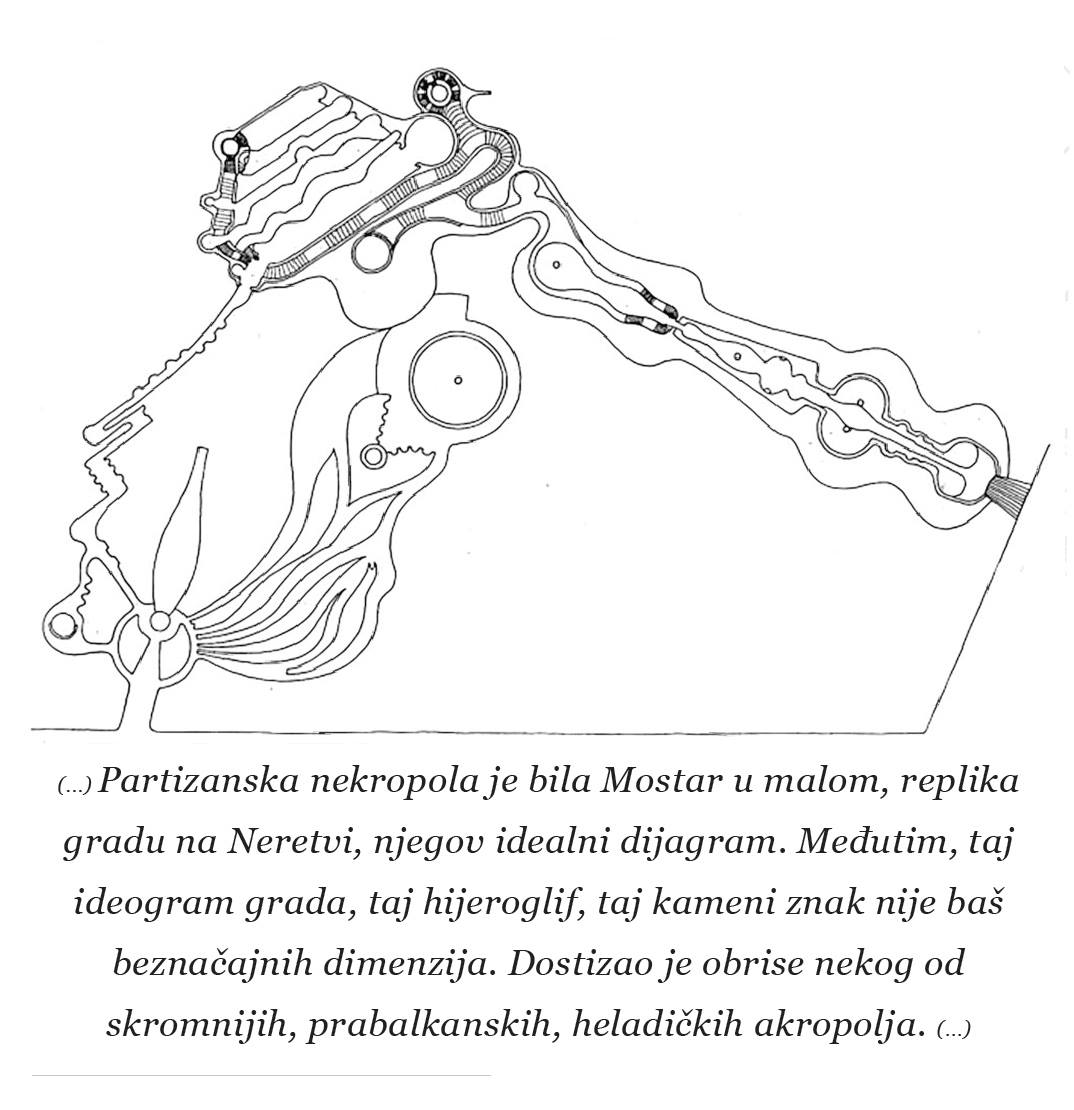

The monument was built slowly, painstakingly, from voluntary contributions, even from contributions in kind (and “in kind” meant stone), and even from old Mostar houses, which time and urbanization were already largely demolishing, so families were gladly donating stone material. Even this quiet relocation of material, and even matter of the old city, had symbolic value.

Stone, often, with centuries-old traces of smoke or with calcified moss, with “housekeepers”, transferred from one time to another particles of memory and the spirit of piety and mixed with the overwhelming quantities of freshly extracted limestone, white as cheese.

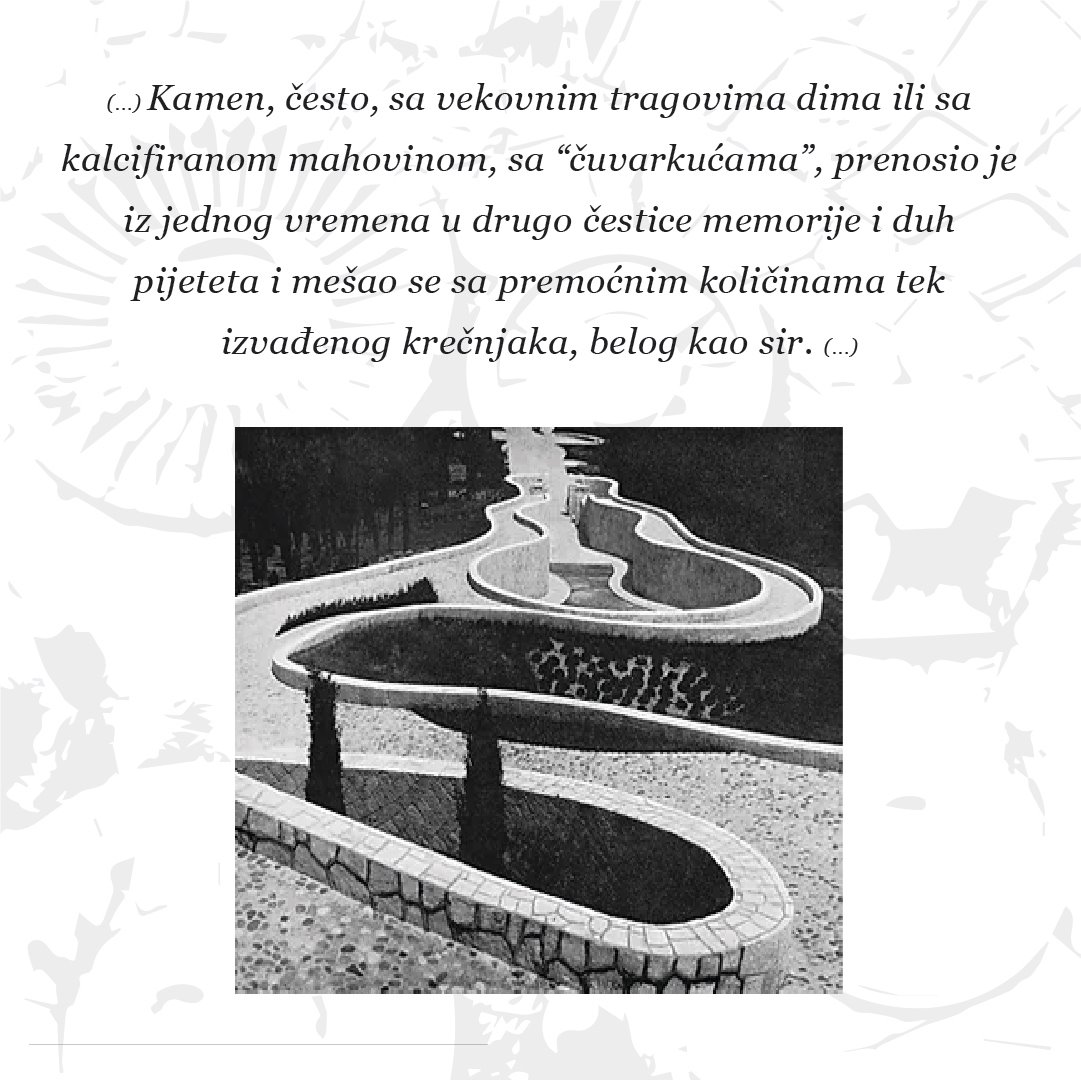

On the upper terraces, on the stone inner walls of the “city”, on the folds of stone walls: semi-circular niches (halbskreisformige Nische), apses (Apsido), buttresses (Mauer und Strebepfeiler) – hundreds and hundreds of stone flowers were scattered. Since I at least half believed in the ancient prejudice of builder-alchemists that limestone is the child of the sun and the moon and that it is precisely for this reason extremely favorable, even predetermined for carving celestial phenomena, so with stone flowers celestial representations of the sun, moon, planets, constellations were abundantly mixed. There was somewhere a place even for the constellation of the Big Dog, which I never managed to find in the sky, and even for a group of stars, which does not exist on the celestial carpet, and which I in my imagination called “Seven skinny cows”. For the uninitiated, these were Pleiades (Plejaden, Siebengestirn) …

In the end, it turned out that the Partisan necropolis as a whole resembled a large astrological model from which we all unanimously, and in the greatest enthusiasm, read the best future.

The singing, pagan character of the Partisan necropolis could not go unnoticed. Its terraces were soon conquered by children, whose cheerful voices on the ringing, almost scenic stone space echoed sometimes deep into the night. All that I could still wish for I generously received, a little in jest, and a little in reality, and that is the right to be an honorary citizen of Mostar, to the left of the entrance gate, to foresee a hidden small niche for my future stone urn…

But, as things stand now, I would no longer be in the company of my friends, the plates with their names were carefully, cold-bloodedly, sadistically picked up, taken away and ground in a stone mill. And all that remains of my original promise is that the former city of the dead and the former city of the living still look at each other, but they look at each other with empty, black, burned eyes.

(The text was published in the Mostar information magazine MM, in the double issue 12/13, in June 1997.)

source: https://www.tacno.net/kultura/bogdan-bogdanovic-mostarski-grad-mrtvih/ , https://abrasradio.info/grad-mojih-prijatelja-bogdan-bogdanovic/